How Does The Saudi Fintech Landscape Compare To The Global Scene?

Racing With The Giants

Discussions around the impact that financial technology (Fintech) holds within the Saudi startup ecosystem has been springing up in different entrepreneurial circles throughout the year. Investors are intrigued, non-fintech entrepreneurs feel the burn, and for the Saudi landscape, $347 million in total venture capital (VC) funds solely deposited in one sector, and over the period of 12 months, is relatively massive.

In the first half of this year alone, Saudi fintech startups raised 1700% more venture capital compared the year before, according to the UAE-based data platform MAGNiTT.

Despite shaking up the local scene, these figures parallel a global record in fintech investment whereby $91.5 billion in global funding was invested into the sector between January and October of this year, bringing the total of global fintech unicorns to 200 startups.

To have the local scene resemble a global movement is both reassuring and overwhelming. It provides Saudi entrepreneurs and investors with enough confidence to aim for global records and opens a range of possible comparisons between the local and the international ecosystems. In particular, it highlights how, in comparison to the weariness that is starting to lurk around US and UK-based venture capital firms as they double startup valuations at a faster rate than ever recorded in the past decade, Saudi-based investors and startups appear more positive when it comes to the resilience of the ecosystem in general.

Many local founders and VC partners believe capital is safely abundant, and rising VC valuations of Saudi and global fintech startups does not seem to worry or deter Saudi investors from continuing to place a bulk of their capital, and overall interest, into the sector, eager to support startups not old enough to mark their first year.

Tamara & The Case For International Investors

Tamara, the fast-growing Saudi-based fintech that was founded in 2020, offers a payment solution highly popularized among users: the Buy Now Pay Later (BNPL) service. Customers seem to like the convenience of not having to worry about payment upfront and despite the anxiety among global regulators who believe the model leads to user debts and late fees, the service still dominates over other fintech solutions. Tamara's ability to secure partnerships with both online and offline retailers - including IKEA, Abyat, Golden Scent, Namshi, and SHEIN - presents a strong case for the current prevalence of BNPL within the Saudi landscape.

Interestingly, tamara's highest investor and the one who drove the startup's monumental Series A round is Checkout.com, a US-based fintech company whose investment in tamara is the first geographical expansion the company leads in the Middle East.

This reflects an interesting phenomenon that seems to be taking shape across the Mena region where a growing foreign VC interest in Saudi startups is aligning with the nation-wide push to encourage international companies to establish a stronger physical and economic presence within the Saudi market.

Having global firms participate alongside Saudi VCs will not only drives competition within the local startup ecosystem, heightening the performance measures for Saudi firms, but it can also open comparisons between Saudi VCs and global ones. In the fintech space, this adds another layer of pressure to catch up with both investment trends and regulatory debates that are taking place presently in the US and the UK around topics like the usefulness of Buy Now Pay Later (BNPL) solutions, the legality of digital assets and cryptocurrency, or more generally, the true role of the fintech regulator.

A Global Regulatory Battle

Particularly after the surge in fintech investments post-covid 19, regulatory bodies in the US and the UK have become skeptical about the market dominance that fintech startups have achieved and what that could mean for the wider economy. In his annual shareholder letter published last April, Jamie Dimon, the CEO of JP Morgan Chase, appears cautious in his approach towards the sector as he places both 'Fintech' and 'Big Tech' under the subtitle, "Banks Enormous Competitive Threats - from Virtually Every Angle".

The letter clearly agrees with the importance of "open competition", but nonetheless acknowledges the impact that fintech and big tech companies, including Amazon and Google, are starting to have on traditional banks. Even though Chase is in a strong position economically, as a company backed by the biggest US investment bank by assets ($2.6 trillion), and as an active player who acquired 3 fintech startups so far - OpenInvest, Nutmeg, and 55ip - the anxiety that Chase holds towards the fintech sector reflects the general attitude shared by financial regulators not only in the US financial, legal, and political circles but also arguably worldwide.

Even though traditional banks are generally known for being less receptive to disruptive innovation, one of the ways they can consider to address their increasing uneasiness towards fintech is by choosing to become more active participants in the sector rather than avoid, or ultimately fight, fintech startups. As they enter the space, banks have the potential to re-balance the market share between fintech startups and financial institutions, even providing exit opportunities for these startups.

This is the current direction in the Saudi ecosystem, as regulators have agreed to license two digital banks - STC Bank (by STC Pay) and the Saudi Digital Bank - to "realize the Vision 2030 objectives and support the banking sector growth", as stated by the Saudi Central Bank (SAMA).

It might be true that the choice to allow STC Pay, an already well-established company, to form a digital bank rather than support an emerging local startup to have its own bank is rooted in a desire to hold the brakes on the lesser regulated banking startup subsector, but the decision to issue licenses on its own is a positive move that reveals an encouraging Saudi regulatory system. Saudi fintech startups are finding regulatory and government bodies open to form partnerships and to work hand in hand to advance the local scene, which uniquely differentiates the Saudi landscape from the typically glorified US and UK startup ecosystems.

Working with Regulators: The Saudi case

In 2019, SAMA began offering open enrollment for fintech startups wishing to test their market solutions under minimum risk through its formal Regulatory Sandbox program. Offered via Fintech Saudi, a fintech hub established in collaboration between SAMA and the Capital Markets Authority (CMA), the Sandbox granted licenses to 32 Saudi and non-Saudi fintech startups to experiment their solutions under the 6-months testing cycle, and allowed 16 fintech companies to operate in the kingdom.

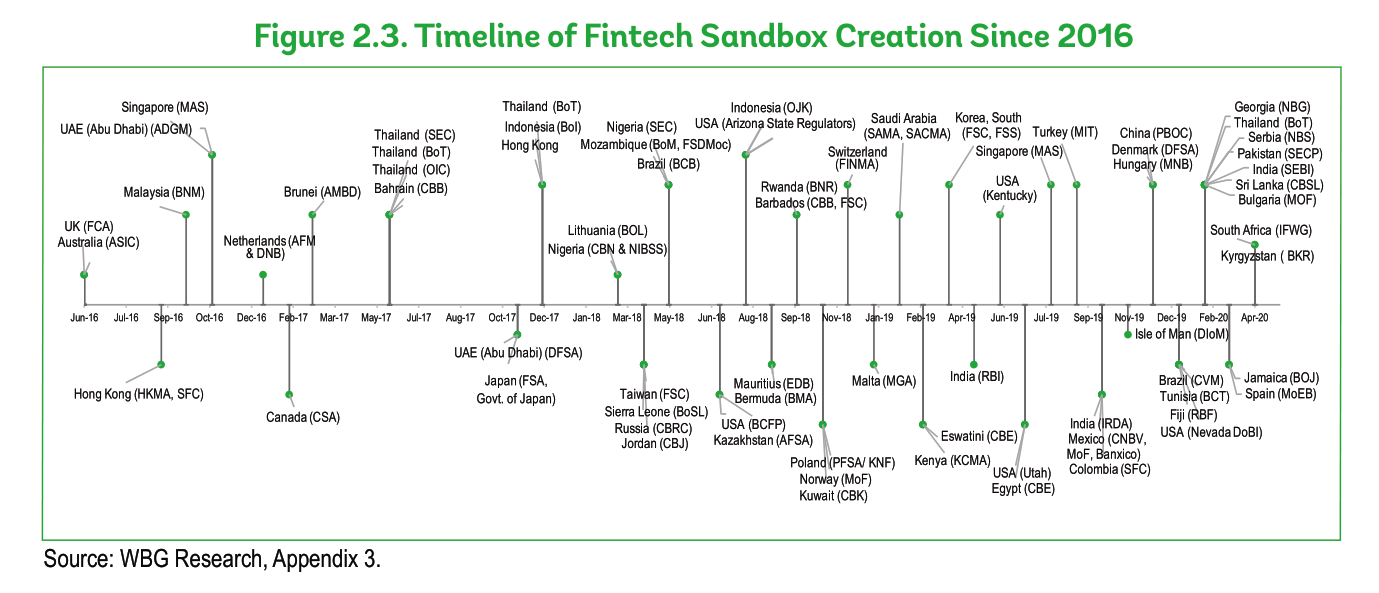

To what extent enrolling in the Sandbox program helps startups achieve market scalability and sustainable post-graduation growth is still early to assess, since the program only ran five cohorts so far and registered startups seem to present a small percentage of the 82 total fintech startups in Saudi Arabia. This nascency is shared worldwide too, as regulatory sandboxes have only been established six years ago, which makes it hard to thoroughly assess the initiative.

Having said that, Sandboxes did show positive effects in emerging markets, according to the data by the World Bank, and especially in regions whose regulatory measures are yet to mature. As a key benefit, they can assist with building private and public partnerships for startups and accelerate their market entry by authorizing them to operate under revised capital requirements.

In Saudi Arabia, private partnerships gave rise to the success behind Geidea, Saudi's largest fintech firm, the only non-bank company to be added to the national payments system (Mada) alongside STC pay, and the first company in the region to provide contactless, app-based, payment services. Before it's enrollment in Mada, Geidea signed an agreement with MasterCard last April, allowing it to offer its contactless, tap-on-phone, payment feature. This sets the example for the importance to seek collaborative opportunities before, if not via, meeting regulators.

Such partnership opportunities, plausible to secure under Sandbox programs, allow disruptive startups to acquire the confidence needed as they continue to explore what market strategies work best for the Saudi economy.

With time, the Saudi fintech wave will crystalize more and more, pushing the limits of digital financial innovation and regulatory maturity. Perhaps, the collaborative relationship between startups and the central bank will shape a less controversial Saudi financial landscape compared to US and UK markets, one that is supportive of the emerging technologies and is, at the same time, desirably protective of its legacy financial establishments.